Identify underperforming machines instantly with the slot floor heat map Super Graphic™, and other innovative visual analytics tools Optimize multi-games on the floor easily through detailed multi-game performance analysis reporting and hierarchical treemap Super Graphic™.

Learning Objectives

- Outline the principles of operant conditioning.

- Explain how learning can be shaped through the use of reinforcement schedules and secondary reinforcers.

In classical conditioning the organism learns to associate new stimuli with natural, biological responses such as salivation or fear. The organism does not learn something new but rather begins to perform in an existing behavior in the presence of a new signal. Operant conditioning, on the other hand, is learning that occurs based on the consequences of behavior and can involve the learning of new actions. Operant conditioning occurs when a dog rolls over on command because it has been praised for doing so in the past, when a schoolroom bully threatens his classmates because doing so allows him to get his way, and when a child gets good grades because her parents threaten to punish her if she doesn’t. In operant conditioning the organism learns from the consequences of its own actions.

How Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior: The Research of Thorndike and Skinner

Psychologist Edward L. Thorndike (1874–1949) was the first scientist to systematically study operant conditioning. In his research Thorndike (1898) observed cats who had been placed in a “puzzle box” from which they tried to escape (video). At first the cats scratched, bit, and swatted haphazardly, without any idea of how to get out. But eventually, and accidentally, they pressed the lever that opened the door and exited to their prize, a scrap of fish. The next time the cat was constrained within the box it attempted fewer of the ineffective responses before carrying out the successful escape, and after several trials the cat learned to almost immediately make the correct response.

Observing these changes in the cats’ behavior led Thorndike to develop his law of effect, the principle that responses that create a typically pleasant outcome in a particular situation are more likely to occur again in a similar situation, whereas responses that produce a typically unpleasant outcome are less likely to occur again in the situation (Thorndike, 1911). The essence of the law of effect is that successful responses, because they are pleasurable, are “stamped in” by experience and thus occur more frequently. Unsuccessful responses, which produce unpleasant experiences, are “stamped out” and subsequently occur less frequently.

Video Clip: Thorndike’s Puzzle Box. When Thorndike placed his cats in a puzzle box, he found that they learned to engage in the important escape behavior faster after each trial. Thorndike described the learning that follows reinforcement in terms of the law of effect. https://youtu.be/BDujDOLre-8

The influential behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) expanded on Thorndike’s ideas to develop a more complete set of principles to explain operant conditioning. Skinner created specially designed environments known as operant chambers (usually called Skinner boxes) to systemically study learning. A Skinner box (operant chamber) is a structure that is big enough to fit a rodent or bird and that contains a bar or key that the organism can press or peck to release food or water. It also contains a device to record the animal’s responses.

The most basic of Skinner’s experiments was quite similar to Thorndike’s research with cats. A rat placed in the chamber reacted as one might expect, scurrying about the box and sniffing and clawing at the floor and walls. Eventually the rat chanced upon a lever, which it pressed to release pellets of food. The next time around, the rat took a little less time to press the lever, and on successive trials, the time it took to press the lever became shorter and shorter. Soon the rat was pressing the lever as fast as it could eat the food that appeared. As predicted by the law of effect, the rat had learned to repeat the action that brought about the food and cease the actions that did not.

Skinner studied, in detail, how animals changed their behavior through reinforcement and punishment, and he developed terms that explained the processes of operant learning (Table 7.1). Skinner used the term reinforcer to refer to any event that strengthens or increases the likelihood of a behavior and the term punisher to refer to any event that weakens or decreases the likelihood of a behavior. And he used the terms positive and negative to refer to whether a reinforcement was presented or removed, respectively. Thus positive reinforcementstrengthens a response by presenting something pleasant after the response and negative reinforcementstrengthens a response by reducing or removing something unpleasant. For example, giving a child praise for completing his homework represents positive reinforcement, whereas taking aspirin to reduced the pain of a headache represents negative reinforcement. In both cases, the reinforcement makes it more likely that behavior will occur again in the future.

| Operant conditioning term | Description | Outcome | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive reinforcement | Add or increase a pleasant stimulus | Behavior is strengthened | Giving a student a prize after he gets an A on a test |

| Negative reinforcement | Reduce or remove an unpleasant stimulus | Behavior is strengthened | Taking painkillers that eliminate pain increases the likelihood that you will take painkillers again |

| Positive punishment | Present or add an unpleasant stimulus | Behavior is weakened | Giving a student extra homework after she misbehaves in class |

| Negative punishment | Reduce or remove a pleasant stimulus | Behavior is weakened | Taking away a teen’s computer after he misses curfew |

Reinforcement, either positive or negative, works by increasing the likelihood of a behavior. Punishment, on the other hand, refers to any event that weakens or reduces the likelihood of a behavior. Positive punishment weakens a response by presenting something unpleasant after the response, whereas negative punishment weakens a response by reducing or removing something pleasant. A child who is grounded after fighting with a sibling (positive punishment) or who loses out on the opportunity to go to recess after getting a poor grade (negative punishment) is less likely to repeat these behaviors.

Although the distinction between reinforcement (which increases behavior) and punishment (which decreases it) is usually clear, in some cases it is difficult to determine whether a reinforcer is positive or negative. On a hot day a cool breeze could be seen as a positive reinforcer (because it brings in cool air) or a negative reinforcer (because it removes hot air). In other cases, reinforcement can be both positive and negative. One may smoke a cigarette both because it brings pleasure (positive reinforcement) and because it eliminates the craving for nicotine (negative reinforcement).

It is also important to note that reinforcement and punishment are not simply opposites. The use of positive reinforcement in changing behavior is almost always more effective than using punishment. This is because positive reinforcement makes the person or animal feel better, helping create a positive relationship with the person providing the reinforcement. Types of positive reinforcement that are effective in everyday life include verbal praise or approval, the awarding of status or prestige, and direct financial payment. Punishment, on the other hand, is more likely to create only temporary changes in behavior because it is based on coercion and typically creates a negative and adversarial relationship with the person providing the reinforcement. When the person who provides the punishment leaves the situation, the unwanted behavior is likely to return.

Creating Complex Behaviors Through Operant Conditioning

Perhaps you remember watching a movie or being at a show in which an animal—maybe a dog, a horse, or a dolphin—did some pretty amazing things. The trainer gave a command and the dolphin swam to the bottom of the pool, picked up a ring on its nose, jumped out of the water through a hoop in the air, dived again to the bottom of the pool, picked up another ring, and then took both of the rings to the trainer at the edge of the pool. The animal was trained to do the trick, and the principles of operant conditioning were used to train it. But these complex behaviors are a far cry from the simple stimulus-response relationships that we have considered thus far. How can reinforcement be used to create complex behaviors such as these?

One way to expand the use of operant learning is to modify the schedule on which the reinforcement is applied. To this point we have only discussed a continuous reinforcement schedule, in which the desired response is reinforced every time it occurs; whenever the dog rolls over, for instance, it gets a biscuit. Continuous reinforcement results in relatively fast learning but also rapid extinction of the desired behavior once the reinforcer disappears. The problem is that because the organism is used to receiving the reinforcement after every behavior, the responder may give up quickly when it doesn’t appear.

Most real-world reinforcers are not continuous; they occur on a partial (or intermittent) reinforcement schedule—a schedule in which the responses are sometimes reinforced, and sometimes not. In comparison to continuous reinforcement, partial reinforcement schedules lead to slower initial learning, but they also lead to greater resistance to extinction. Because the reinforcement does not appear after every behavior, it takes longer for the learner to determine that the reward is no longer coming, and thus extinction is slower. The four types of partial reinforcement schedules are summarized in Table 7.2.

| Reinforcement schedule | Explanation | Real-world example |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-ratio | Behavior is reinforced after a specific number of responses | Factory workers who are paid according to the number of products they produce |

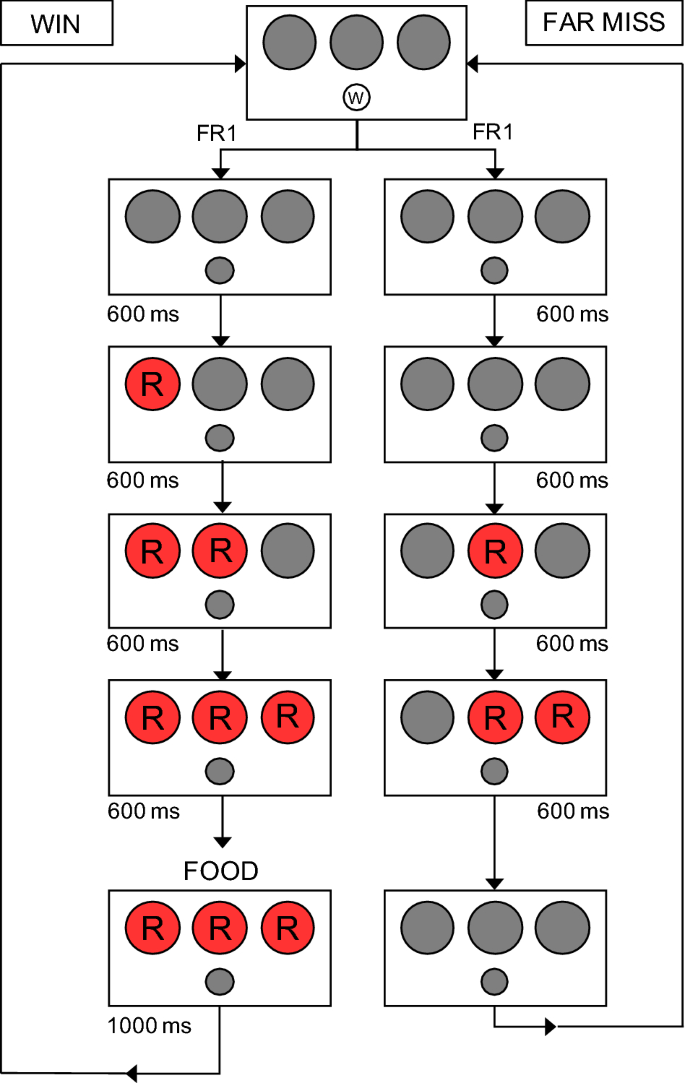

| Variable-ratio | Behavior is reinforced after an average, but unpredictable, number of responses | Payoffs from slot machines and other games of chance |

| Fixed-interval | Behavior is reinforced for the first response after a specific amount of time has passed | People who earn a monthly salary |

| Variable-interval | Behavior is reinforced for the first response after an average, but unpredictable, amount of time has passed | Person who checks voice mail for messages |

Partial reinforcement schedules are determined by whether the reinforcement is presented on the basis of the time that elapses between reinforcement (interval) or on the basis of the number of responses that the organism engages in (ratio), and by whether the reinforcement occurs on a regular (fixed) or unpredictable (variable) schedule. In a fixed-interval schedule, reinforcement occurs for the first response made after a specific amount of time has passed. For instance, on a one-minute fixed-interval schedule the animal receives a reinforcement every minute, assuming it engages in the behavior at least once during the minute. As you can see in Figure 7.7, animals under fixed-interval schedules tend to slow down their responding immediately after the reinforcement but then increase the behavior again as the time of the next reinforcement gets closer. (Most students study for exams the same way.) In a variable-interval schedule, the reinforcers appear on an interval schedule, but the timing is varied around the average interval, making the actual appearance of the reinforcer unpredictable. An example might be checking your e-mail: You are reinforced by receiving messages that come, on average, say every 30 minutes, but the reinforcement occurs only at random times. Interval reinforcement schedules tend to produce slow and steady rates of responding.

In a fixed-ratio schedule, a behavior is reinforced after a specific number of responses. For instance, a rat’s behavior may be reinforced after it has pressed a key 20 times, or a salesperson may receive a bonus after she has sold 10 products. As you can see in Figure 7.7, once the organism has learned to act in accordance with the fixed-reinforcement schedule, it will pause only briefly when reinforcement occurs before returning to a high level of responsiveness. A variable-ratio schedule provides reinforcers after a specific but average number of responses. Winning money from slot machines or on a lottery ticket are examples of reinforcement that occur on a variable-ratio schedule. For instance, a slot machine may be programmed to provide a win every 20 times the user pulls the handle, on average. As you can see in Figure 7.8, ratio schedules tend to produce high rates of responding because reinforcement increases as the number of responses increase.

Complex behaviors are also created through shaping, the process of guiding an organism’s behavior to the desired outcome through the use of successive approximation to a final desired behavior. Skinner made extensive use of this procedure in his boxes. For instance, he could train a rat to press a bar two times to receive food, by first providing food when the animal moved near the bar. Then when that behavior had been learned he would begin to provide food only when the rat touched the bar. Further shaping limited the reinforcement to only when the rat pressed the bar, to when it pressed the bar and touched it a second time, and finally, to only when it pressed the bar twice. Although it can take a long time, in this way operant conditioning can create chains of behaviors that are reinforced only when they are completed.

Reinforcing animals if they correctly discriminate between similar stimuli allows scientists to test the animals’ ability to learn, and the discriminations that they can make are sometimes quite remarkable. Pigeons have been trained to distinguish between images of Charlie Brown and the other Peanuts characters (Cerella, 1980), and between different styles of music and art (Porter & Neuringer, 1984; Watanabe, Sakamoto & Wakita, 1995).

Behaviors can also be trained through the use of secondary reinforcers. Whereas a primary reinforcer includes stimuli that are naturally preferred or enjoyed by the organism, such as food, water, and relief from pain, a secondary reinforcer (sometimes called conditioned reinforcer) is a neutral event that has become associated with a primary reinforcer through classical conditioning. An example of a secondary reinforcer would be the whistle given by an animal trainer, which has been associated over time with the primary reinforcer, food. An example of an everyday secondary reinforcer is money. We enjoy having money, not so much for the stimulus itself, but rather for the primary reinforcers (the things that money can buy) with which it is associated.

Key Takeaways

- Edward Thorndike developed the law of effect: the principle that responses that create a typically pleasant outcome in a particular situation are more likely to occur again in a similar situation, whereas responses that produce a typically unpleasant outcome are less likely to occur again in the situation.

- B. F. Skinner expanded on Thorndike’s ideas to develop a set of principles to explain operant conditioning.

- Positive reinforcement strengthens a response by presenting something that is typically pleasant after the response, whereas negative reinforcement strengthens a response by reducing or removing something that is typically unpleasant.

- Positive punishment weakens a response by presenting something typically unpleasant after the response, whereas negative punishment weakens a response by reducing or removing something that is typically pleasant.

- Reinforcement may be either partial or continuous. Partial reinforcement schedules are determined by whether the reinforcement is presented on the basis of the time that elapses between reinforcements (interval) or on the basis of the number of responses that the organism engages in (ratio), and by whether the reinforcement occurs on a regular (fixed) or unpredictable (variable) schedule.

- Complex behaviors may be created through shaping, the process of guiding an organism’s behavior to the desired outcome through the use of successive approximation to a final desired behavior.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Give an example from daily life of each of the following: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, negative punishment.

- Consider the reinforcement techniques that you might use to train a dog to catch and retrieve a Frisbee that you throw to it.

- Watch the following two videos from current television shows. Can you determine which learning procedures are being demonstrated?

- The Office: www.break.com/usercontent/2009/11/the-office-altoid- experiment-1499823

- The Big Bang Theory: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JA96Fba-WHk

References

Cerella, J. (1980). The pigeon’s analysis of pictures. Pattern Recognition, 12, 1–6.

Porter, D., & Neuringer, A. (1984). Music discriminations by pigeons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 10(2), 138–148;

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. New York, NY: Macmillan. Retrieved from http://www.archive.org/details/animalintelligen00thor

Watanabe, S., Sakamoto, J., & Wakita, M. (1995). Pigeons’ discrimination of painting by Monet and Picasso. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 63(2), 165–174.

Purpose

This document provides guidance interpreting the requirements of the Bank Secrecy Act ('BSA') regulations1 as they apply to the casino and card club industries in the United States.

Section A: 31 C.F.R. § 103.11 Casino and Card Club Definitions2

Question 1: What gaming institutions are subject to the BSA casino regulatory requirements?

Answer 1: A casino or a card club that is duly licensed or authorized to do business as such, and has gross annual gaming revenue in excess of $1 million, is a 'financial institution' under the BSA. The definition applies to both land-based and riverboat operations licensed or authorized under the laws of a state, territory,3 or tribal jurisdiction, or under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.4 Tribal gaming establishments that offer slot machines, video lottery terminals, or table games,5 and that have gross annual gaming revenue in excess of $1 million are covered by the definitions. Card clubs generally are subject to the same rules as casinos, unless a different treatment for card clubs is explicitly stated in 31 C.F.R. Part 103.

Question 2: Is a tribal gaming establishment that offers only bingo and related games considered a casino for purposes of the BSA?

Answer 2: No. FinCEN has the authority under the BSA to define as 'casinos' tribal gaming establishments that offer only bingo and related games. Nevertheless, in addressing the treatment of tribal gaming under the BSA, we have indicated that 'activities such as bingo . . . are not generally offered in casino-like settings and may create different problems for law enforcement, tax compliance, and anti-money laundering programs than do full-scale casino operations.'6 FinCEN does not view tribal gaming establishments that offer only traditional bingo (i.e., not contained in electronic gaming devices) and related games in non-casino settings as satisfying the definition of 'casino' for purposes of the BSA.

However, a tribal gaming establishment that offers both bingo and slot machines or table games, for example, would satisfy the definition of 'casino,' if gross annual gaming revenue exceeds $1 million. All gaming activity must go into the calculation of gross annual gaming revenue, including activity that standing alone would not transform an establishment into a casino. This is the same treatment that FinCEN applies to a state-licensed casino that offers poker (which is a non-house banked game) since poker and a poker room are an integral part of a casino operation.7

Question 3: Is a 'racino' considered a gaming institution subject to the BSA?

Answer 3: The term 'racino' has not been separately defined nor included specifically in the definition of casino for purposes of the BSA. In general, the term refers to horse racetracks that may be authorized under state law to engage in or offer a variety of collateral gaming operations, including slot machines, video lottery terminals, video poker or card clubs. FinCEN relies on the state, territory or tribal characterization of 'racino' gaming in determining whether an entity or operation should be treated as a casino for purposes of the BSA. If state law defines or characterizes slot machine or video lottery operation at a racetrack as a 'casino, gambling casino, or gaming establishment,' and the gross annual gaming revenues of that operation exceed the $1 million threshold, then the operation would be deemed to be a 'casino' for purposes of the BSA and subject to all applicable requirements.8

Question 4: Would a race book or sports pool operator that has a 'nonrestricted' Nevada gaming license be considered a casino for purposes of the BSA?

Answer 4: Yes. Operators or owners of a Nevada race book or sports pool,9 that are duly issued a 'nonrestricted' Nevada gaming license,10 and that have gross annual gaming revenues in excess of $1 million are subject to the casino requirements under 31 C.F.R. Part 103, as well as all other applicable BSA requirements. This would include a Nevada race book or sports pool licensee that obtained a 'nonrestricted' gaming license to operate a race book or sports pool on the property of another casino, or that operates a number of satellite race books and sports pools that are affiliated with a central site book.

Question 5: Is an establishment that offers only off-track betting on horse races considered a casino for purposes of the BSA?

Answer 5: In addressing the treatment of tribal gaming under the BSA, we have indicated that 'pari-mutuel wagering' should receive the same treatment as bingo when determining whether an establishment satisfies the definition of 'casino.' 11 Furthermore, Class III gaming under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act includes off-track betting on horse races.12 In addition, in Nevada, an establishment that offers only off-track betting on horse races would need to obtain a non-restricted gaming license. In many instances, off-track betting on horse races will involve pari-mutuel wagering. However, pari-mutuel wagering also applies to sporting events. For purposes of the BSA, FinCEN views casinos to include establishments in Nevada and in tribal jurisdictions that offer only off-track betting, provided the establishments permit account wagering and provided gross annual gaming revenue exceeds $1 million.13 In many instances, off-track betting will involve accounts through which customers may conduct a variety of transactions, including wagers, deposits, withdrawals, and transfers of funds. As we recognized when addressing the treatment of tribal gaming under our rules, FinCEN has sought to apply the BSA to 'gaming establishments that provide both gaming and an array of financial services for their patrons.'14

Question 6: Are 'greyhound racing clubs' that offer table games considered gaming institutions for purposes of the BSA?

Answer 6: If a 'greyhound racing club'15 generates gross annual gaming revenue in excess of $1 million from poker tables (which would be akin to offering card games in a card club or card room type operation), and if the gaming facility is duly licensed or authorized by a state or local government to do business as a card club, gaming club, card room, gaming room, or similar gaming establishment, it would be subject to the BSA.16 Therefore, once the $1 million in revenue threshold is exceeded for such poker tables, all gaming activity must go into the calculation of gross annual gaming revenue, including activity that standing alone would not deem an establishment a casino, such as greyhound racing at the track, simulcast for other greyhound racing tracks, simulcast for horse racing tracks, or simulcast for jai alai.

Question 7: Are horse racetracks that offer pari-mutuel or other forms of wagering only on races held at the track considered casinos for purposes of the BSA?

Answer 7: FinCEN does not view a horse racetrack that offers pari-mutuel or other forms of wagering only on races held at the track as a casino for purposes of the BSA. We believe that, under these circumstances, wagering is integral to hosting the race itself. Horse racing as an industry poses 'different problems for law enforcement, tax compliance, and anti-money laundering programs than do full-scale casino operations.'17

Section B: 31 C.F.R. § 103.22 Currency Transaction Reporting Requirements18

Question 8: Is a casino required to provide identification information on customers who have conducted reportable multiple currency transactions that were summarized through 'after the fact aggregation?'

Answer 8: The process of checking internal casino computer information, rating cards, general ledgers, and other books and records after the end of the gaming day to find reportable currency transactions is sometimes referred to as 'after the fact aggregation.' After the fact aggregation of currency transactions does not relieve a casino of the requirement to file a FinCEN Form 103 Currency Transaction Report by Casinos ('CTRC') on reportable multiple transactions containing all information required when it has the ability to obtain customer identification information through reviewing internal records in paper or electronic form or through automated data processing systems. The anti-money laundering compliance program requirement obligates a casino or card club to use all available information to determine a customer's name, address, and Social Security number19 from any existing information system or other system of records for a reportable multiple transaction summarized through 'after the fact aggregation' when a customer is no longer available.20 Also, for casinos or card clubs with automated data processing systems, programs for compliance with the BSA must provide for the use of these systems to aid in assuring compliance.21

Therefore, when a casino or card club cannot obtain identification information on reportable multiple transactions because a customer is no longer available, it must check its internal records or systems, including federal forms and records, which contain verified customer information. These records may include credit, deposit, or check cashing account records, or a previously filed CTRC form, IRS Form W-2G (Certain Gambling Winnings), or any other tax or other form containing such customer information. If a casino files a CTRC form lacking some customer identification information in situations described above, it would be required to file an amended CTRC with new identification information on the initial transaction if the customer returns and conducts new transactions of which a casino obtains knowledge.22

Question 9: Is a casino required to use customer currency transaction information contained in the casino's slot monitoring system for purposes of BSA currency transaction reporting?

Answer 9: For purpose of the BSA, FinCEN does not view customer 'coin-in' and 'coin-out'23 transactions at a slot machine or video lottery terminal to be reportable as currency transactions because they can represent so-called 'recycled' coin transactions (i.e., casino customers typically engaging in transactions deriving from the same coins just won at electronic gaming devices). If a casino were to use 'coin-in' and 'coin-out' information in its slot monitoring system, it would distort and result in incorrect reporting of currency transactions. However, when a casino has knowledge of customer 'paper money' transactions for slot club accountholders identified through its slot monitoring system, it must aggregate these with other types of 'cash in' transactions of which the casino has knowledge and which are recorded on a casino's books and records to determine whether the currency transactions exceed $10,000 for a customer in a gaming day.24 When a casino has knowledge of multiple currency transactions conducted by or on behalf of the same customer on the same day, it is required to treat those multiple transactions as a single reportable transaction for purposes of determining whether currency transaction reporting requirements have been met. Therefore, the conclusions that apply to the aggregation of two or more transactions involving the insertion of bills into slot machines also would apply to the aggregation of such transactions with other categories of 'cash in' transactions.

It is not necessary to have personally observed the transactions; knowledge can also be acquired from a casino examining the books, records, logs, computer files, etc., that contain information that the currency transactions have occurred after the gaming day is over. Although FinCEN regulations impose no requirement to examine books or records merely for purposes of aggregating transactions in currency and determining whether to file a report on FinCEN Form 103, BSA requirements other than the requirement to report transactions in currency may obligate a casino to examine computerized records. A casino must report transactions that the casino 'knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect' are suspicious and implement procedures reasonably designed to assure the detection and proper reporting of suspicious transactions.25 For casinos with automated data processing systems, automated programs for compliance with the BSA must provide for the use of these systems to aid in assuring compliance,26 including identifying transactions that appear to be suspicious conducted by customers using their magnetic club account cards at slot machines or video lottery terminals.27

Also, casinos should note that activities such as: (i) 'turning off the dollar counter' to prevent obtaining knowledge of reportable transactions (i.e., not using the feature that is readily available in its software program that accumulates U.S. dollars that a customer inserts into a slot machine bill acceptor while using a magnetic slot club account card), or (ii) requesting that a vendor remove a software tool or interface capability from its next software upgrade could result in enforcement action under the BSA.28

Question 10: Is a cash wager/bet that is ultimately lost at a table game considered a transaction in currency for purposes of BSA currency transaction reporting?

Answer 10: Casinos are required under BSA regulations to file currency transaction reports for 'cash in' transactions, which include 'bets of currency.' For purposes of the currency transaction reporting requirements, a cash bet (referred to as a 'money play')29 at a table game would become a 'bet of currency' once the customer can no longer retrieve the bet (e.g., once the dealer has dealt the cards). The cash wager would be a 'cash in' transaction for purposes of currency transaction reporting regardless of whether the customer subsequently wins or loses the wager.30

However, money plays are exempted as reportable cash in transactions to the extent the customer wagers the same physical currency that the customer wagered on a prior money play on the same table game, and the customer has not departed from the table.31 Also, money plays are exempted as reportable cash out transactions when the currency used to place the wager is the same physical currency received when the customer wins the bet.32

Question 11: Is a card club required to maintain and retain records of all currency transactions by customers pertaining to backline betting for purposes of currency transaction reporting?

Answer 11: Yes. The BSA requires card clubs to maintain and to retain the original or a microfilm copy of records of all currency transactions by customers, including without limitation, records in the form of currency transaction logs and multiple currency transaction logs.33 This requirement applies to card clubs34 that offer the practice of backline betting. Backline betting occurs when a customer, who is standing behind a seated player, places a bet or wager on the betting circle for a specific hand on which a seated player also is wagering. The extra players that stand behind each seat position are known as 'backline betters.' Although backline betting makes it difficult to track customer wagers at the gaming table, a card club must have a procedure in place to identify such transactions for purposes of filing a FinCEN Form 103 (CTRC).35

A card club must have procedures for using all available information to determine and verify, when required, the name, address, social security or taxpayer identification number, and other identifying information for a person.36 In addition, a card club employee or propositional player37 who obtains actual knowledge (i.e., direct and clear awareness of a fact or condition) of unknown customers exchanging currency and chips with each other during poker/card game play in excess of $10,000 in currency, through a single transaction or through a series of transactions in a gaming day, would be required to comply with suspicious activity reporting.

In addition, the BSA requires card clubs to prepare a record of any transaction required to be retained, if the record is not otherwise produced in the ordinary course of business.38 Therefore, when a card club employee or propositional player monitoring a non-house banked card game has obtained actual knowledge of a reportable currency transaction, he/she is required to produce a record of the transaction for purposes of currency transaction reporting and a card club must retain such record for a period of five years.

Question 12: Is a casino required to file FinCEN Form 103 (CTRC) on slot jackpot wins in excess of $10,000 in currency?

Answer 12: FinCEN no longer requires a casino to file a FinCEN Form 103 (CTRC), when it has knowledge of customer slot jackpot wins involving payment in currency in excess of $10,000 (e.g., through a single transaction or through aggregating transactions on multiple transaction logs, W-2G issued log). This BSA currency reporting requirement was amended by 31 C.F.R. § 103.22(b)(2)(iii)(D), which removed jackpots from slot machines or video lottery terminals from the definition of 'cash out' transactions.39

Question 13: In the instructions to FinCEN Form 103, what does the word 'periodically' mean when updating customer identification information for casino customers granted accounts for credit, deposit, or check cashing, or for whom a CTRC containing verified identity has been filed?

Answer 13: The General Instructions to FinCEN Form 103 (CTRC), under 'Identification requirements' state:

For casino customers granted accounts for credit, deposit, or check cashing, or on whom a CTRC containing verified identity has been filed, acceptable identification information obtained previously and maintained in the casino's internal records may be used as long as the following conditions are met. The customer's identity is reverified periodically, any out-of-date identifying information is updated in the internal records, and the date of each reverification is noted on the internal record. For example, if documents verifying an individual's identity were examined and recorded on a signature card when a deposit or credit account was opened, the casino may rely on that information as long as it is reverified periodically.

As part of the requirement to establish an effective system of internal controls,40 a casino or card club must determine how often it will reverify a customer's identity to update the identifying information in the internal record for purposes of currency transaction reporting. Given this requirement, it is a common business practice for casinos to maintain a 'known customer' file containing a customer's name, address and identification credential that it has previously verified.41 Accordingly, a casino or card club checks Item 27b on FinCEN Form 103 to indicate that it has examined an acceptable internal casino record (i.e., credit, deposit, or check cashing account record, or a CTRC worksheet) containing previously verified identification information on a 'known customer.' There is no fixed period that will apply to all casinos for all types of customers. The purpose of this requirement is to keep customer identification information reasonably current. Hence, a casino should develop its own policies based on its own experiences with how often relevant customer information, such as permanent address or last name, might change.

Section C: 31 C.F.R. § 103.21 Suspicious Transaction Reporting Requirements

Question 14: How comprehensive must a casino's procedures be for detecting suspicious activity?

Answer 14: A casino or card club is responsible for establishing and implementing risk-based internal controls (i.e., policies, procedures and processes) to comply with the BSA42 and to safeguard its operations from money laundering and terrorist financing, including for detecting, analyzing and reporting potentially suspicious activity. A casino or card club is required to file a suspicious activity report for a transaction when it knows, suspects or has reason to suspect that the transaction or pattern of transactions (conducted or attempted) is both suspicious, and involves $5,000 or more (in the single event or when aggregated) in funds or other assets. The extent and specific parameters under which a casino or card club must monitor customer accounts43 and transactions for suspicious activity must factor in the type of products and services it offers, the locations it serves, and the nature of its customers. In other words, suspicious activity monitoring and reporting systems cannot be 'one size fits all.'

As part of its internal controls, a casino or card club must establish procedures for using all available information, including its automated systems44 and its surveillance system and surveillance logs, to determine the occurrence of any transactions or patterns of transactions required to be reported as suspicious.45 Also, a casino or card club must perform appropriate due diligence in response to indicia of suspicious transactions, using all available information. Please note that a casino or card club must train personnel in the identification of unusual or suspicious transactions.46

Question 15: How can a casino complete suspicious activity reporting ('SAR') for 'unknown' subjects?

Answer 15: Since a casino or a card club is prohibited from disclosing to a customer involved in a suspicious activity that it filed a FinCEN Form 102, Suspicious Activity Report by Casinos and Card Clubs ('SARC'), FinCEN advises using internal records that contain verified customer identification information when filing this form. Such records may include credit, deposit, or check cashing account records or any filed FinCEN Form 103 (CTRC), FinCEN Form 103-N, Currency Transaction Report by Casinos - Nevada, IRS Form W-2G, Certain Gambling Winnings, or IRS Form W-9, Request for Taxpayer Identification Number and Certification.

If the above records or reports do not exist or if additional customer identification information is needed to complete the form, FinCEN advises casinos and card clubs to use any other records that may be on file which contain verified identification such as a driver's license, military or military dependent identification cards, passport, non-resident alien registration card, state issued identification card, foreign national identity card (e.g., cedular card), other government-issued document evidencing nationality or residence and bearing a photograph or similar safeguard, or a combination of other unexpired documents, which contain an individual's name and address and preferably a photograph. If casinos or card clubs do not have verified identification information on the customer, they should use whatever other sources of customer information are available within internal records, such as player rating records, slot club membership records, a filed IRS Form 1099-Misc, Miscellaneous Income (e.g., pertaining to prizes or awards), or a filed IRS Form 1042-S, Foreign Person's U.S. Source Income Subject to Withholding, etc.

If no suspect is identified on the date of detection, a casino or card club may delay filing a SARC form for an additional 30 calendar days to identify a suspect. However, a casino or card club must in all events report a suspicious transaction within 60 calendar days after the date of initial detection (regardless of whether a casino or card club is able to identify a suspect).

Question 16: Must a casino identify suspicious customer chip redemptions at a cage for reporting on FinCEN Form 102 (SARC)?

Answer 16: A casino must implement procedures reasonably designed to assure the detection and proper reporting of suspicious transactions.47 Also, a casino shall file a report of each transaction in currency involving cash out of more than $10,000 in a gaming day in which it has obtained knowledge including the redemption of chips.48 A casino, which is not required by state or tribal regulations to maintain multiple currency transaction logs or currency transaction logs at the casino cage,49 nonetheless should develop an internal control50 based on a risk analysis to be able to identify chip redemptions that were paid with currency from the imprest drawer51 to a customer52 that involve potential suspicious transactions to assure ongoing BSA compliance. Such an internal control would aid such casinos in monitoring chip redemptions for 'unknown' customers who previously purchased chips and then engaged in minimal or no gaming activity for purposes of suspicious activity reporting.53 As a corollary, a casino should develop an internal control, based on a risk analysis, to be able to identify betting ticket,54 token,55 and TITO ticket56 redemptions that were paid with currency from an imprest drawer to a customer that involve potential suspicious transactions to assure ongoing BSA compliance.

Moreover, the BSA requires casinos to prepare and retain a record of any transaction that is not otherwise produced in the ordinary course of business to comply with these regulations.57 Also, records must in all events be filed or stored in such a way as to be accessible within a reasonable period of time.58 A casino must retain such record of the transaction for a period of five years.

Question 17: What type of information has law enforcement found to have particular value on FinCEN Form 102 (SARC)?

Answer 17: Casinos and card clubs should note the type of information contained on a FinCEN Form 102 (SARC) that law enforcement has advised is the most valuable to them, and which, if missing, limits the effectiveness for law enforcement use.

- Provide complete subject identifying information, such as name, permanent address, government-issued identification number, date of birth, and casino account number.

- Identify the characterization of suspicious activity by checking Item 26 on the form and refrain from checking the 'other' box unless the activity is not covered by the existing list of suspicious activities.

- Prepare a concise and clear narrative that provides a complete description of the suspicious activity. The following are several things to consider when a casino or card club reviews a SARC's narrative (i.e., Part VI) to ensure it is concise and clear:

- - Provides a detailed description of the suspicious activity.

- - Narrative should not state, 'see attached.'

- - Identifies 'who,' 'what,' 'when,' 'why,' 'where,' and 'how.'

- - Identifies whether the transaction was attempted or completed.

- - Is chronological and complete.

- - Identifies the dates of any previously filed Form 102 on the same subject.

- - Notes any actions (taken or planned) by the casino, including any internal investigative numbers used by the casino to maintain records of the suspicious activity.

- Include contact information for persons at the casino with additional information about the suspicious activity.

For additional guidance on providing a clear and complete description of the suspicious activity, see FinCEN's Suspicious Activity Reporting Guidance for Casinos.

Question 18: Should a casino or card club document the basis for its determination that a transaction is not suspicious?

Answer 18: If a casino determines that an activity is suspicious, it must file FinCEN Form 102 (SARC). However, based on the available facts and after an initial investigation, a casino may determine that certain unusual activity is not suspicious. Although 31 C.F.R. § 103.21 does not specifically state that a casino or a card club must document the reasons why it has not filed FinCEN Form 102 for a particular activity that was reviewed as potentially suspicious, it is an effective practice for a casino or card club to document the basis for its determination that the transaction is not, after all, suspicious.59

Thorough documentation provides a record of the decision-making process (including the final decisions not to file a SARC) which a casino or card club would find helpful to: (i) assist internal or external auditors and examiners in their assessment of the effectiveness of its suspicious activity reporting and monitoring and reporting system, (ii) assist its internal review committee60 in making future decisions on what should be reported as suspicious, (iii) train employees about what transactions are suspicious and which are not suspicious based on all the relevant facts and circumstances, (iv) respond to a potential law enforcement subpoena pertaining to a particular customer whose activity was reviewed by the committee, but considered not to be suspicious, and (v) if it has multiple casino properties in the same jurisdiction, ensure that reasonably consistent suspicious activity reporting risk-based analysis procedures are being followed.

Section D: 31 C.F.R. § 103.36 Casino Recordkeeping Requirements

Question 19: What specific recordkeeping requirements apply to a casino?

Answer 19: 31 C.F.R. § 103.36 requires a casino or card club to maintain and to retain the following source records (either the originals or microfilm version, or other copies or reproductions of the documents) that relate to its operation:

- Records of each deposit of funds, account opened or line of credit extended, including a customer's identification and the verification of that identification as well as similar information for other persons having a financial interest in the account, regardless of residency;

- Records of each receipt showing transactions for or through each customer's deposit or credit account, including a customer's identification and the verification of that identification, regardless of residency;

- Records of each bookkeeping entry comprising a debit or credit to a deposit account or credit account;

- Statements, ledger cards or other records of each deposit or credit account, showing each transaction in or with respect to the deposit or credit account;

- Records of each extension of credit in excess of $2,500, including a customer's identification and the verification of that identification, regardless of residency;

- Records of each advice, request or instruction with respect to a transaction of any monetary value involving persons, accounts or places outside the United States, including customer identification, regardless of residency;

- Records prepared or received in the ordinary course of business that would be needed to reconstruct a customer's deposit or credit account;

- Records required by other governmental agencies, e.g., federal, state, local or tribal;

- A list of transactions involving various types of instruments, cashed or disbursed, in face amounts of $3,000 or more, regardless of whether currency is involved, including customer's name and address; and

- A copy of the compliance program required by 31 C.F.R. § 103.64.

Also, card clubs are required to maintain and to retain records of all currency transactions by customers, including, without limitation, records in the form of currency transaction logs and multiple currency transaction logs.

Besides the above casino-specific requirements, there are other BSA recordkeeping requirements that apply to all financial institutions, including casinos and card clubs, such as:

- Records by persons having financial interests in foreign financial accounts;61

- Records of transmittals of funds in excess of $3,000 requiring the verification of identity, and the recording, retrievability and reporting of information to other financial institutions in the payment chain, regardless of the method of payment;62 and

- Nature of records, record access, and five-year retention period for records.63

Question 20: What computer records must a casino retain?

Answer 20: A casino or card club that inputs, stores, or retains, in whole or in part, for any period of time, any record required to be maintained by 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.33 or 103.36(a) and (b) on computer disk, tape, or other machine-readable media shall retain the records in such media. Also, a casino or card club is required to maintain the indexes, books, file descriptions and programs that would enable a person readily to access and review these computer records. These computerized records, source documentation and related programs must be retained for a period of five years. However, the BSA does not require that computerized records be stored in on-line memory in a computer past their normal business use.64 Nonetheless, records must in all events be filed or stored in such a way as to be accessible within a reasonable period of time,65 taking into consideration the nature of the records and the length of time since the record was made.

A casino may not delete or destroy specific computerized customer gaming activity information (prior to the end of the five-year retention period), such as player rating records,66 and instead only retain the more limited trip history records (which only summarize the total funds from a customer's multi-day trip and the most recent trips, usually between three and nine trips). Because a trip includes any number of continuous days of gaming activity in which there is not a break in play, the player trip history is only a limited summarized record that typically does not provide all of the information contained on the original rating card, such as the specific amounts of the customer's currency transactions conducted for each gaming day.

Further, the retention of computerized records does not relieve a casino from the obligation to retain any record required to be maintained by 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.33 or 103.36(a) and (b), which typically are the source documents (either the originals or microfilm version, or other copies or reproductions of the documents) of customers' transactions.

Section E: 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a) Compliance Program Requirements67

Question 21: How comprehensive must an internal and/or external testing program be to assure and monitor compliance with the BSA?

Answer 21: A casino or card club must conduct internal and/or external testing for compliance with a scope and frequency commensurate with the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing it faces, as well as the products and services it provides, to determine if a casino's procedures are comprehensive enough to detect suspicious activity.68

The primary objectives of the independent testing of the BSA compliance program are to determine whether: (i) the program is properly designed and operating effectively to comply with suspicious and currency transaction reporting, identification, recordkeeping, and record retention requirements; (ii) there are material weaknesses (e.g., inadequate training) and internal control deficiencies; (iii) testing of the program is based on risk assessment criteria designed to focus on money laundering and terrorist financing as well as the products and services provided; and (iv) there is adherence to BSA policy, procedures, and systems.

FinCEN is aware that some casinos conduct internal testing for BSA compliance on a regular basis as part of their annual internal audit plan. The testing provides an assessment of the level of BSA compliance. The internal audit report typically includes the scope, objectives, and findings of the audit as well as a response to any audit finding indicating the corrective action to be taken, the target date for completion, and the department head responsible for the corrective action. Other casinos and card clubs may hire independent certified public accountants for similar purposes.

A casino or card club needs to take corrective actions once becoming aware of weakness and deficiencies in its anti-money laundering compliance program, or any element thereof, that could or did result in failures to comply with BSA identification, reporting, recordkeeping, record retention as well as compliance program requirements. Violations of these regulatory requirements may result in both criminal and civil penalties.

Question 22: What type of compliance training program should be developed and what types of documentation should be maintained by a casino or card club to ensure that it has an adequate, accurate, and complete program?

Answer 22: One of the more important elements of the anti-money laundering compliance program is the obligation to institute an effective and ongoing training program for all appropriate casino or card club personnel. Such a compliance training program should be commensurate with the risks posed by the products and financial services provided. Training should be provided to all personnel before conducting financial transactions on behalf of a casino at the cage (including casino credit and slot booth), on the floor (including table games, keno, poker, other floor games, and slot machines/video lottery terminals), as well as those responsible for complying with BSA currency transaction and suspicious transaction reporting, identification, recordkeeping, and other compliance program requirements. Also, a casino or card club is required to maintain, and to retain, a copy of the compliance program documentation. This documentation should include all casino records, documents, and manuals substantiating the training program as well as the training of appropriate personnel.69 The requirement is flexible and allows each compliance training program to depend on the characteristics of an individual casino. For example, a large casino having many table games, slot machines/video lottery terminals, and cage windows might need a more comprehensive training program than a small casino with no table games. A compliance procedures manual for employees should cover all applicable divisions or departments (e.g., table games, slot operations, keno, poker), other operational departments (e.g., cage operations, casino credit, slot booth), as well as other departmental functions (e.g., accounting, finance, information technology, marketing, surveillance).

Also, recordkeeping procedures should reflect the types of financial services provided. In addition, the training program should ensure that casino front-line employees, such as cage personnel (e.g., shift managers), cage cashiers, front window cashiers (i.e., general cashiers), pit personnel (e.g., pit bosses), floor persons (i.e., raters), dealers, and slot personnel (e.g., slot supervisors, slot attendants, slot cashiers, change persons) have appropriate training to detect the occurrence of unusual or suspicious casino transactions.

Question 23: What does the requirement mean that casinos that have automated data processing systems must use their automated programs to aid in assuring compliance?

Answer 23: Casinos are required to 'develop and implement' written programs that are reasonably designed to assure BSA compliance with all applicable requirements.70 Effective casino anti-money laundering compliance procedures should include identifying and using appropriate automated systems and programs71 for all applicable gambling operating divisions or departments (e.g., table games, slots, keno, poker), other operational departments (e.g., cage, slot booth), as well as other departmental functions (e.g., accounting, surveillance) to comply with suspicious activity and currency transaction reporting, as well as to maintain relevant records72 for casino accountholders.73

Questions or comments regarding the contents of this Guidance should be addressed to the FinCEN Regulatory Helpline at 800-949-2732.

1See 31 C.F.R. Part 103.

2See 31 U.S.C. § 5312(a)(2)(X) and 31 C.F.R. § 103.11(n)(5)(i) and (n)(6)(i).

3This includes casinos located in Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, St. Croix (U.S. Virgin Islands), and Tinian (Northern Mariana Islands). See 31 C.F.R. § 103.11(tt).

4The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act is codified at 25 U.S.C. § 2701 et seq.

5Slot machines, video lottery terminals, and house-banked table games would qualify as Class III gaming under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. Bingo and related games, including pull tabs, lotto, punch boards, tip jars, instant bingo and some card games, would qualify as Class II gaming under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

6See 61 F.R. 7054 - 7056 (February 23, 1996).

7Id.

8A similar conclusion would apply to 'racinos' operating in tribal jurisdictions. Slot machines, table games, and similar forms of gaming would qualify as either Class II or Class III gaming under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

9The Nevada Gaming Commission issues 'nonrestricted' gaming licenses to operators or owners of Nevada race book or sports pools. See Nevada Gaming Commission Regulation 22.020. A Nevada race book 'means the business of accepting wagers upon the outcome of any event held at a track which uses the pari-mutuel system of wagering.' See Nevada Revised Statute § 463.01855. A Nevada race book is a business that accepts wagers at fixed odds (or track odds) based on the outcome of the race that may be televised and displayed in Nevada casinos (i.e., 'simulcasting'). A Nevada sports pool 'means the business of accepting wagers on sporting events by any system or method of wagering.' See Nevada Revised Statute § 463.0193. A Nevada sports pool is a business that accepts wagers at fixed odds based on the outcome of certain professional and amateur athletic sporting events that may be televised and displayed in Nevada casinos.

10A Nevada 'nonrestricted license' includes, among other things, '. . . A license for, or operation of, any number of slot machines together with any other game, gaming device, race book or sports pool at one gaming establishment.' See Nevada Revised Statute § 463.0177(2). In addition, Nevada Revised Statute § 463.245(3) provides an exception to the prohibition against having more than one licensee issued to each casino. Also, see Nevada Gaming Commission Regulation 22.010(4).

11See 61 F.R. 7054 - 7056 (February 23, 1996).

12We have already addressed a situation in which an establishment operating in a tribal jurisdiction offers off-track betting on horse races and other Class III gaming. See In the Matter of the Tonkawa Tribe of Oklahoma and Edward E. Street - FinCEN No. 2006-1 (March 24, 2006).

13This discussion addresses off-track betting in Nevada and tribal jurisdictions only. Off-track betting may not require a gaming license in other jurisdictions. The definition of 'casino' includes only those establishments licensed or authorized to conduct business as casinos.

14See 61 F.R. 7054 - 7056 (February 23, 1996).

15A greyhound racing club is a gaming establishment that offers the sport of racing greyhounds. Specially trained dogs chase a lure (which is an artificial hare or rabbit) around an oval track until they arrive at the finish line. The dog that arrives first in each event is the winner of the bet.

16See 31 U.S.C. § 5312(a)(2)(X) and 31 C.F.R. § 103.11(n)(6)(i). The class of gaming establishments known as 'card clubs' became subject to the BSA as of August 1, 1998. See 63 F.R. 1919 - 1924 (Jan. 13, 1998).

17See 61 F.R. 7054 --7056 (February 23, 1996).

18See 31 C.F.R. § 103.22(b)(2) and (c)(3).

19See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(v)(A).

20However, FinCEN does recognize that for certain aggregate currency transactions, a casino may not be able to obtain the required customer identification information because either the customer has left the casino and is no longer available or a casino does not have internal records which provide all of the required customer identification information.

21See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(vi).

22See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.22(b)(2) and (c)(3), 103.27(a) and (d), and 103.28. Also, see FinCEN Form 103, Specific Instructions, Item 1, for filing an amended report.

23Coin-in is a metered count of coins, credits and other amounts bet by customers at an electronic gaming device. Coin-out is a metered count of coins, credits and other amounts paid out to customers on winnings at an electronic gaming device. Therefore, coin-in does not include paper currency inserted into a bill acceptor (on slot machine or video lottery terminal) to accumulate credits.

24See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.22(b)(2)(i)(I), (b)(2)(iii)(C), and (c)(3), and 103.64(b)(3) and (4).

25See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.21 and 103.64(a)(2)(v)(B).

26See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(vi).

27Furthermore, as discussed in FinCEN Ruling 2005-1, measures that a casino could implement in response to a risk-based suspicious activity analysis could include enhancements to the operating system for slot machines. The enhancements could consist of new software tools/interfaces and reprogramming. A casino could develop the enhancements or have a vendor develop the enhancements.

28See 31 U.S.C. § 5321(a)(1) and 31 C.F.R. § 103.57(f).

29See 31 C.F.R. § 103.22(b)(2)(i)(E).

30See FinCEN Administrative Ruling FIN-2006-R002, A Cash Wager on Table Game Play Represents a 'Bet of Currency' (March 24, 2006).

31Nonetheless, when a customer increases a subsequent cash bet (i.e., money play) at the same table without departing, the increase in the amount of the currency bet would represent a new bet of currency and a transaction in currency being monitored by a casino.

32See 31 C.F.R. § 103.22(b)(2)(iii)(B) and 72 F.R. 35008 (June 26, 2007).

33See 31 C.F.R. § 103.36(b)(11).

34The card clubs operate or run the games and earn their revenue by receiving a fee from, rather than 'banking,' the games as casinos do. See 63 F.R. 1919 - 1924 (January 13, 1998). 31 C.F.R. § 103.116(n)(6)(i) defines a card club as a card club, gaming club, card room, gaming room, or similar gaming establishment.

35See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.22(b)(2) and (c)(3), 103.28, and 103.64(a)(2)(i) and (b)(3) - (4).

36See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(v)(A).

37A propositional player is a natural person employed by a casino or card club to play a permissible game with his or her personal funds. A propositional player is paid a fixed sum by a casino or card club for playing in a poker/card game and retains any winnings and absorbs any losses. Also, a propositional player's function is to start and gamble at a poker/card game, to keep a sufficient number of players in a game, or to keep the action going in a game. Some card rooms have entered into contractual agreements with so-called 'third party provider[s] of propositional player services' to exclusively bank poker/card games as independent contractors, which introduces issues with assuring day-to-day BSA compliance with maintaining currency and cash equivalent records. An individual employed by such a service is called a 'third party propositional player' who gambles with funds provided by such a service.

38See 31 C.F.R. § 103.38(b).

39See 72 F.R. 35008 (June 26, 2007).

40See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(i).

41Typically, these records contain the original method of identification (including type, number and expiration date, of the customer's identification credential originally examined) and the date of such examination as well as a photocopy or other reproduction (e.g., a computerized representation) of the identification credential. Some casinos maintain hard copy internal records and others digitized records containing identification information on a known customer.

42See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.64(a) and 103.120(d).

43Types of casino accounts that would be subject to suspicious activity reporting include deposit (i.e., safekeeping, front money or wagering), credit, check cashing, player rating or tracking, and slot club accounts.

44See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(vi).

45See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(v)(B).

46See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(iii).

47See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(v)(B).

48See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.22(b)(2)(ii)(A) and (c)(3), and 103.64(b)(4).

49Almost all casinos maintain multiple transaction logs ('MTLs') pursuant to state, tribal or local laws, or as unique business records. Casinos or card clubs record on these logs only currency transactions above a given threshold, usually $2,500 - $3,000. Also, some casinos have enhanced the existing MTL compliance procedure to require a surveillance photograph of each 'unknown' customer to assist in identifying customers for purposes of aggregating transactions for currency transaction reporting as well as potential suspicious transaction reporting.

50See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(2)(i).

51Casinos and card clubs maintain cages where cashiers conduct financial transactions using a drawer that operates on an imprest basis or inventory. An imprest basis is a method of accounting for funds inventories whereby any replenishment or removal of funds is accounted for by an exchange of an exact amount of other funds in the inventory. The imprest drawer opens with a stated amount of currency and/or chips. Any subsequent additions or removal of funds in the drawer are accounted for by either a document or an exchange of an equal amount of funds of another form. Since chips and currency are fungible items no imprest records of these transactions are prepared or maintained.

52For example, a known customer with a casino deposit (i.e., safekeeping, front money or wagering), credit, check cashing, player rating/player tracking, or slot club account.

53See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.21 and 103.64(a)(2)(v)(B).

54A betting ticket is a written record of a wager for a race or sporting event. It is printed with a unique ticket number and is used to record the event for which the wager was placed. It includes the name of the gambling establishment, race or sport event (e.g., race track, race number, horse identification), the amount of the wager, line or spread, and date and time. The gambling establishment provides a copy of the betting ticket to a customer and maintains a record of it.

55A token is a gaming instrument or coin issued by a casino at certain stated denominations as a substitute for currency and used to play certain slot machines or video lottery terminals. Tokens are most often used for denominations of $1.00 or greater. Tokens represent a monetary value only within the casino and are intended for the purposes of gambling.

56Slot machines or video lottery terminals that print tickets are commonly known as 'ticket in/ticket out' or 'TITO' machines. A TITO ticket is a gaming instrument issued by a slot machine or video lottery terminal to a customer as a record of the wagering transaction and/or substitute for currency. Tickets are voucher slips printed with the name and the address of the gaming establishment, the stated monetary value of the ticket, date and time, machine number (i.e., asset or location), an 18-digit validation number, and a unique bar code. Tickets are a casino bearer 'IOU' instrument. A customer can use a ticket at a machine or terminal that accepts tickets, or cash a ticket at a cage, slot booth, a redemption kiosk, or a pari-mutuel window at the gaming establishment.

5731 C.F.R. § 103.38(b) states that 'records required by this subpart to be retained by financial institutions may be those made in the ordinary course of business by a financial institution. If no record is made in the ordinary course of business of any transaction with respect to which records are required to be retained by this subpart, then such a record shall be prepared in writing by the financial institution.'

58See 31 C.F.R. § 103.38(d).

59See FinCEN's Suspicious Activity Reporting Guidance for Casinos, December 2003, page 4.

60 Many casinos have an internal SARC review committee.

61See 31 C.F.R. § 103.32.

62See 31 C.F.R. § 103.33(f) and (g).

63See 31 C.F.R. § 103.38.

64For example, for casinos that maintain computerized records, such as daily player rating records, markers issued records, and cage voucher records for each customer deposit, deposit withdrawal and marker redemption, they may store such information on-line in computer memory or in off-line storage media, such as magnetic tape, magnetic disk, magnetic diskette, CD-ROM disk, etc.

65See 31 C.F.R. § 103.38(d).

66See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.36(b)(8) and 103.36(c), and F.R. 1165 - 1167 (January 12, 1989).

67See 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.64 and 103.120(d).

68See 31 C.F.R. § 103.21.

69Such training program documentation would include any course outlines, the dates that training was provided, names of personnel who received training, any test that was administered, and the test results to allow internal and/or external examiners to evaluate the effectiveness of each training session.

Slot Machines Maintained Behavior Through Reinforcement

70See 31 C.F.R. § 103.64(a)(1).

71This would include gaming computer systems or other computer systems that interface with systems that track, control, or monitor customer gaming activity (e.g., a casino management system, a casino marketing system, a customer master file system, a credit management system).

72See e.g., 31 C.F.R. §§ 103.21, 103.22(b)(2) and (c)(3), 103.33(f) and (g), and 103.36.

Slot Machines Maintain Behavior Through

73Many companies have developed casino management system software capable of identifying and aggregating customer transactions that are associated with casino accounts such as deposit (i.e., safekeeping, front money, or wagering), credit, check cashing, player rating or tracking, or slot club.